|  |

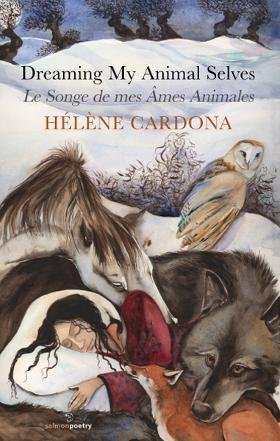

The short poem, Dreams Like Water, which introduces Hélène Cardona’s compelling new poetry collection, Dreaming My Animal Selves (Salmon Poetry, 2013), sets out her main poetic theme in just seven, succinct lines. She will trace and reveal patterns "through beings disguised" (her imagined, imaginative "animal selves") in a desire to unify the disparate parts of the psyche and give it safe, spiritual anchorage. Hers is a quest for healing and wholeness in a dreaming sleep.

And one cannot help but be astonished at how many separate strands there are to Cardona’s own biographical self. Her mother was part Greek, part Irish; her father is Spanish (and a distinguished poet too). She has lived all over Europe and America, and is fluent in six languages (as she writes in her poem Dancing the Dream: "I am the wandering child.") She is or has been an equestrian, dancer, dream analyst, astrologer, yoga practitioner, translator, interpreter, pianist, scholar, assistant professor and actress. Many different selves, indeed.

Cardona’s own life and background, therefore, are as protean as the shape-shifting nature of her poems, and her physical life and soul life weave themselves seamlessly together through the symbols and mythologies in her poetry.

You can detect all kinds of influences here – Romanticism, Surrealism, Freudian and Jungian psychology, the mysticism of Rumi and Blake, Gnosticism, the Yeatsian Celtic Twilight – yet the poetic and soulful path she follows is uniquely her own. This is shamanic poetry, poetry as magic, poetry as a gateway to the unconscious and to the dream world, liminal poetry ("that state of in-betweenness / where even objects seem alive, / to do with light and looking pure"), poetry as alchemy, poetry as healing.

In the early poems of the collection she recalls her childhood: her mother (". . . a shiver down my mother’s / spine was worth a thousand words") and her father ". . . the melancholy in my father’s eyes, / reflecting Lake Geneva, was indecipherable ") and her connection with books and fairy tales, which created for her "an elfin world".

She tries to protect a firm identity (". . . I remain a thistle, resilient, / rooted in Mediterranean Celtic fringe"), yet at the same time she is ". . . insubstantial, chameleon, / excavated like a talisman from wreckage." This split (a dualism both individual and part of the universal human condition) resolves itself in her dreams, her soul voyages, her morphing "animal selves" ("I . . . discover that in dreaming / lies the healing of earth. In dreaming / we travel to a place where all is forgiven.") This is the place of the "Magician", of the "Divine", of the "Immortals"; a place where ". . . experience is cellular. / In our normal state we’re not able to perceive, / that’s why I think the dead know."

Dreaming My Animal Selves is a collection of poems which deserves to be widely available and widely read. It’s certainly one I’ll read over and over, and will appeal to spiritual seekers and lovers of mysticism everywhere.

"The ultimate aim is reverence for the universe. / The ultimate aim is love for life. / The ultimate aim is harmony within oneself." From Isle of the Immortals by Hélène Cardona.

(Dreaming My Animal Selves is a bilingual collection in both English and French.)

RUTH MOWRY on MORELLE SMITH's In Memoriam Will Smith 1882-1916

When I read Morelle's poems for the current issue of TPT I was just so impressed with her abilities.

In both In Memoriam Will Smith 1882-1916 and Musée Flaubert, Rouen (and also in the three posted in the autumn issue) she demonstrates a style and skill that I like most in a poet: she manages language unaffectedly, allowing an occasional lush word to stud a line with sparkle. Were she to use such language more often (as some often do), her poems would lose their grace and power.

In In Memoriam she lets simple Anglo-Saxon words do her work, and though "jetty" is lovely in the first stanza, it is the line "swag bags of rain slung" that gives the first clue of what she is about. And more follow: "slate", "grey", "shouts", "train", "chain", "swamp", and then she sprinkles them with a few simple multi-syllable words like "clamorous", "cellophane" and "capstan". Because she withholds a need to gush, her straightforward use of language allows a few foreign words and proper names to be just the right garnish: "politesse", "Albert", "Amiens", and the wonderful "Picardie".

The poem itself is just tremendous. Never once does she say what relation this person is to her, but because the last name is Smith, we assume he is a relative. But really it's not only from the name, but also from the great effort to travel so far to this grave, this cemetery, that we know this Will Smith means a great deal to the poet. Though she can't have met the deceased, she treats him as if he is a dear beloved who has just died. The shopkeeper can't know how important these roses are, and that they are not going to be opened by anyone but her. They are a gift for someone dead, someone gone like the bustle of the port, someone longed for because of a connection with all things lost. My goodness, when she compares the train itself to a bouquet – the gift – we know that it is as impermanent as the roses. The headstone is still there, and somehow she wants her gift of red roses, as well as the long journey she took to complete this all-important act, to be as long-lived as the stone. What we realize by the last stanza is that the gravestone, the train, the roses, and the florist shop are merely symbols to memorialize this relative, whoever he is. When she ends with those last lines,

". . . red roses

and the fierce light

lashed to the horizon,

tilting, like a boat at sea",

the imagery is perfection. What can be more impermanent and vulnerable, and beautiful, than a boat at sea? And of course it refers back to the great journey she took across the sea to enact this memorial.

There is so much more to say about this poem. I feel movement, the movement of a life, the thrust of it, like the train, the journey itself to that cemetery. And even though a life, like those roses, gets thrust and stuck into the ground in the end, it is still bobbing on the horizon, like a boat. We don't forget! That life keeps living in us, floating in our memory.

Just brilliant.